Inter-Object Communication

Every non-trivial software is based on objects that need to communicate with each other to meet complex goals. This chapter is about design concepts going first into deep explanations on how the armory will achieve great architectures works and how it should be used.

Blocks

Blocks are the Objective-C version of well-knows constructs called lambdas or closures available in other languages for many years now.

They are a great way to design asynchronous APIs as so:

- (void)downloadObjectsAtPath:(NSString *)path

completion:(void(^)(NSArray *objects, NSError *error))completion;

When designing something like the above, try to declare functions and methods to take no more than one block and always make the blocks be the last arguments. It is a good approach to try to combine data and error in one block instead of two separate blocks (usually one for the success and one for the failure).

You should do this because:

- Usually there are part of code that are shared between them (i.e. dismiss a progress or an activity indicator);

- Apple is doing the same, and it is always good to be consistent with the platform;

- Since Blocks are typically multiple lines of code, having the block be other than the last argument would break up the call site[1];

- Taking more than one block as arguments would make the call site potentially unwieldy in length. It also introduces complexity[1].

Consider the above method, the signature of the completion block is very common: the first parameter regards the data the caller is interested in, the second parameter is the error encountered. The contract should be therefore as follow:

- if

objectsis not nil, thenerrormust be nil - if

objectsis nil, thenerrormust not be nil

as the caller of this method is first interested in the actual data, an implementation like so is preferred:

- (void)downloadObjectsAtPath:(NSString *)path

completion:(void(^)(NSArray *objects, NSError *error))completion {

if (objects) {

// do something with the data

}

else {

// some error occurred, 'error' variable should not be nil by contract

}

}

Moreover, as for synchronous methods, some of Apple's APIs write garbage values to the error parameter (if non-NULL) in successful cases, so checking the error can cause false positives.

Under the Hood

Some key points:

- Blocks are created on the stack

- Blocks can be copied to the heap

- Blocks have their own private const copies of stack variables (and pointers)

- Mutable stack variables and pointers must be declared with the __block keyword

If blocks aren't kept around anywhere, will remain on the stack and will go away when their stack frame returns. While on the stack, a block has no effect on the storage or lifetime of anything it accesses. If blocks need to exist after the stack frame returns, they can be copied to the heap and this action is an explicit operation. This way, a block will gain reference-counting as all objects in Cocoa. When they are copied, they take their captured scope with them, retaining any objects they refer. If a block references a stack variable or pointer, then when the block is initialized it is given its own copy of that variable declared const, so assignments won't work. When a block is copied, the __block stack variables it reference are copied to the heap and after the copy operation both block on the stack and brand new block on the heap refer to the variables on the heap.

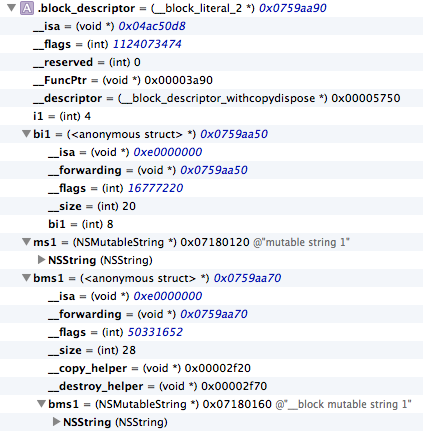

LLDB shows that a block is a nice piece of things.

The most important thing to note is that __block variables and pointers are treated inside the block as structs that obviously handle the reference to the real value/object.

Blocks are first-class citizens in the Objective-C runtime: they have an isa pointer which defines a class through which the Objective-C runtime can access methods and storage. In a non-ARC environment you can mess things up for sure, and cause crashes due to dangling pointers. __block applies only when using the variables in the block, it simply says to the block:

Hey, this pointer or primitive type relies on the stack with its own address. Please refer to this little friend with a new variable on the stack. I mean… refer to the object with double dereference, and don't retain it. Thank you, sir.

If at some time after the declaration but before the invocation of the block, the object has been released and deallocated, the execution of the block will cause a crash. __block variables are not retained within the block. In the deep end… it's all about pointers, references, dereferences and retain count stuff.

Retain cycles on self

It's important not to get into retain cycles when using blocks and asynchronous dispatches. Always set a weak reference to any variable that could cause a retain cycle. Moreover, it is a good practice to nil the properties holding the blocks (i.e. self.completionBlock = nil) this will break potential retain cycle introduced by the block capturing the scope.

Example:

__weak __typeof(self) weakSelf = self;

[self executeBlock:^(NSData *data, NSError *error) {

[weakSelf doSomethingWithData:data];

}];

Not:

[self executeBlock:^(NSData *data, NSError *error) {

[self doSomethingWithData:data];

}];

Example with multiple statements:

__weak __typeof(self)weakSelf = self;

[self executeBlock:^(NSData *data, NSError *error) {

__strong __typeof(weakSelf) strongSelf = weakSelf;

if (strongSelf) {

[strongSelf doSomethingWithData:data];

[strongSelf doSomethingWithData:data];

}

}];

Not:

__weak __typeof(self)weakSelf = self;

[self executeBlock:^(NSData *data, NSError *error) {

[weakSelf doSomethingWithData:data];

[weakSelf doSomethingWithData:data];

}];

You should add these two lines as snippets to Xcode and always use them exactly like this:

__weak __typeof(self)weakSelf = self;

__strong __typeof(weakSelf)strongSelf = weakSelf;

Here we dig further about the subtle things to consider about the __weak and the __strong qualifiers for self inside blocks. To summarize, we can refer to self in three different ways inside a block:

- using the keyword

selfdirectly inside the block - declaring a

__weakreference to self outside the block and referring to the object via this weak reference inside the block - declaring a

__weakreference to self outside the block and creating a__strongreference to self using the weak reference inside the block

Case 1: using the keyword self inside a block

If we use directly the keyword self inside a block, the object is retained at block declaration time within the block (actually when the block is copied but for sake of simplicity we can forget about it) . A const reference to self has its place inside the block and this affects the reference counting of the object. If the block is used by other classes and/or passed around we may want to retain self as well as all the other objects used by the block since they are needed for the execution of the block.

dispatch_block_t completionBlock = ^{

NSLog(@"%@", self);

}

MyViewController *myController = [[MyViewController alloc] init...];

[self presentViewController:myController

animated:YES

completion:completionHandler];

No big deal. But... what if the block is retained by self in a property (as the following example) and therefore the object (self) retains the block?

self.completionHandler = ^{

NSLog(@"%@", self);

}

MyViewController *myController = [[MyViewController alloc] init...];

[self presentViewController:myController

animated:YES

completion:self.completionHandler];

This is what is well known as a retain cycle and retain cycles usually should be avoided. The warning we receive from CLANG is:

Capturing 'self' strongly in this block is likely to lead to a retain cycle

Here comes in the __weak qualifier.

Case 2: declaring a __weak reference to self outside the block and use it inside the block

Declaring a __weak reference to self outside the block and referring to it via this weak reference inside the block avoids retain cycles. This is what we usually want to do if the block is already retained by self in a property.

__weak typeof(self) weakSelf = self;

self.completionHandler = ^{

NSLog(@"%@", weakSelf);

};

MyViewController *myController = [[MyViewController alloc] init...];

[self presentViewController:myController

animated:YES

completion:self.completionHandler];

In this example the block does not retain the object and the object retains the block in a property. Cool. We are sure that we can refer to self safely, at worst, it is nilled out by someone. The question is: how is it possible for self to be "destroyed" (deallocated) within the scope of a block?

Consider the case of a block being copied from an object to another (let's say myController) as a result of the assignment of a property. The former object is then released before the copied block has had a chance to execute.

The next step is interesting.

Case 3: declaring a __weak reference to self outside the block and use a __strong reference inside the block

You may think, at first, this is a trick to use self inside the block avoiding the retain cycle warning. This is not the case. The strong reference to self is created at block execution time while using self in the block is evaluated at block declaration time, thus retaining the object.

Apple documentation reports that "For non-trivial cycles, however, you should use" this approach:

MyViewController *myController = [[MyViewController alloc] init...];

// ...

MyViewController * __weak weakMyController = myController;

myController.completionHandler = ^(NSInteger result) {

MyViewController *strongMyController = weakMyController;

if (strongMyController) {

// ...

[strongMyController dismissViewControllerAnimated:YES completion:nil];

// ...

}

else {

// Probably nothing...

}

};

First of all, this example looks wrong to me. How can self be deallocated and be nilled out if the block itself is retained in the completionHandler property? The completionHandler property can be declared as assign or unsafe_unretained to allow the object to be deallocated after the block is passed around.

I can't see the reason for doing that. If other objects need the object (self), the block that is passed around should retain the object and therefore the block should not be assigned to a property. No __weak/__strong usage should be involved in this case.

Anyway, in other cases it is possible for weakSelf to become nil just like the second case explained (declaring a weak reference outside the block and use it inside).

Moreover, what is the meaning of "trivial block" for Apple? It is my understanding that a trivial block is a block that is not passed around, it's used within a well defined and controlled scope and therefore the usage of the weak qualifier is just to avoid a retain cycle.

As a lot of online references, books (Effective Objective-C 2.0 by Matt Galloway and Pro Multithreading and Memory Management for iOS and OS X by Kazuki Sakamoto & Tomohiko Furumoto) discuss this edge case, the topic is not well understood yet by the majority of the developers.

The real benefit of using the strong reference inside of a block is to be robust to preemption. Going again through the above 3 cases, during the execution of a block:

Case 1: using the keyword self inside a block

If the block is retained by a property, a retain cycle is created between self and the block and both objects can't be destroyed anymore. If the block is passed around and copied by others, self is retained for each copy.

Case 2: declaring a __weak reference to self outside the block and use it inside the block

There is no retain cycle and no matter if the block is retained or not by a property. If the block is passed around and copied by others, when executed, weakSelf can have been turned nil. The execution of the block can be preempted and different subsequent evaluations of the weakSelf pointer can lead to different values (i.e. weakSelf can become nil at a certain evaluation).

__weak typeof(self) weakSelf = self;

dispatch_block_t block = ^{

[weakSelf doSomething]; // weakSelf != nil

// preemption, weakSelf turned nil

[weakSelf doSomethingElse]; // weakSelf == nil

};

Case 3: declaring a __weak reference to self outside the block and use a __strong reference inside the block

There is no retain cycle and, again, no matter if the block is retained or not by a property. If the block is passed around and copied by others, when executed, weakSelf can have been turned nil. When the strong reference is assigned and it is not nil, we are sure that the object is retained for the entire execution of the block if preemption occurs and therefore subsequent evaluations of strongSelf will be consistent and will lead to the same value since the object is now retained. If strongSelf evaluates to nil usually the execution is returned since the block cannot execute properly.

__weak typeof(self) weakSelf = self;

myObj.myBlock = ^{

__strong typeof(self) strongSelf = weakSelf;

if (strongSelf) {

[strongSelf doSomething]; // strongSelf != nil

// preemption, strongSelf still not nil

[strongSelf doSomethingElse]; // strongSelf != nil

}

else {

// Probably nothing...

return;

}

};

In an ARC-based environment, the compiler itself alerts us with an error if trying to access an instance variable using the -> notation. The error is very clear:

Dereferencing a __weak pointer is not allowed due to possible null value caused by race condition, assign it to a strong variable first.

It can be shown with the following code:

__weak typeof(self) weakSelf = self;

myObj.myBlock = ^{

id localVal = weakSelf->someIVar;

};

In the very end:

Case 1: should be used only when the block is not assigned to a property, otherwise it will lead to a retain cycle.

Case 2: should be used when the block is assigned to a property.

Case 3: it is related to concurrent executions. When asynchronous services are involved, the blocks that are passed to them can be executed at a later period and there is no certainty about the existence of the self object.

Delegate and DataSource

Delegation is a widespread pattern throughout Apple's frameworks and it is one of the most important patterns in the Gang of Four's book "Design Patterns". The delegation pattern is unidirectional, the message sender (the delegant) needs to know about the recipient (the delegate), but not the other way around. The coupling between the objects is loosen the sender only knows that its delegate conforms to a specific protocol.

In its pure form, delegation is about providing callbacks to the delegate, which means that the delegate implements a set of methods with void return type.

Unfortunately this has not been respected over years by the APIs from Apple and therefore developers acted imitating this misleading approach. A classic example is the UITableViewDelegate protocol.

While some methods have void return type and look like callbacks:

- (void)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView didSelectRowAtIndexPath:(NSIndexPath *)indexPath;

- (void)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView didHighlightRowAtIndexPath:(NSIndexPath *)indexPath;

others are definitely not:

- (CGFloat)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView heightForRowAtIndexPath:(NSIndexPath *)indexPath;

- (BOOL)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView canPerformAction:(SEL)action forRowAtIndexPath:(NSIndexPath *)indexPath withSender:(id)sender;

When the delegant asks for some kind of information to the delegate object, the direction implied is from the delegate to the delegant and to the other way around anymore. This is conceptually different and a new name should be use to describe the pattern: DataSource.

One could argue that Apple has a UITableViewDataSouce protocol for it (forced under the name of the delegate pattern) but in reality it is used for methods providing information about how the real data should be presented.

- (UITableViewCell *)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView cellForRowAtIndexPath:(NSIndexPath *)indexPath;

- (NSInteger)numberOfSectionsInTableView:(UITableView *)tableView;

Moreover, in the above 2 methods Apple mixed the presentation layer with the data layer which is clearly ugly and in the end very few developers felt bad about it over times and even here we'll call delegate methods both methods with void return type and not void for simplicity.

To split the concepts, the following approach should be used:

- delegate pattern: when the delegant needs to notify the delegate about event occurred

- datasource pattern: when the delegant needs to fetch information from the datasource object

Here is a concrete example:

@class ZOCSignUpViewController;

@protocol ZOCSignUpViewControllerDelegate <NSObject>

- (void)signUpViewControllerDidPressSignUpButton:(ZOCSignUpViewController *)controller;

@end

@protocol ZOCSignUpViewControllerDataSource <NSObject>

- (ZOCUserCredentials *)credentialsForSignUpViewController:(ZOCSignUpViewController *)controller;

@end

@protocol ZOCSignUpViewControllerDataSource <NSObject>

@interface ZOCSignUpViewController : UIViewController

@property (nonatomic, weak) id<ZOCSignUpViewControllerDelegate> delegate;

@property (nonatomic, weak) id<ZOCSignUpViewControllerDataSource> dataSource;

@end

Delegate methods should be always have the caller as first parameter as in the above example otherwise delegate objects could not be able to distinguish between different instances of delegants. In other words, if the caller is not passed to the delegate object, there would be no way for any delegate to deal with 2 delegant object. So, following is close to blasphemy:

- (void)calculatorDidCalculateValue:(CGFloat)value;

By default, methods in protocols are required to be implemented by delegate objects. It is possible to mark some of them as optional and to be explicit about the required method using the @required and @optional keywords as so:

@protocol ZOCSignUpViewControllerDelegate <NSObject>

@required

- (void)signUpViewController:(ZOCSignUpViewController *)controller didProvideSignUpInfo:(NSDictionary *);

@optional

- (void)signUpViewControllerDidPressSignUpButton:(ZOCSignUpViewController *)controller;

@end

For optional methods, the delegant must check if the delegate actually implements a specific method before sending the message to it (otherwise a crash would occur) as so:

if ([self.delegate respondsToSelector:@selector(signUpViewControllerDidPressSignUpButton:)]) {

[self.delegate signUpViewControllerDidPressSignUpButton:self];

}

Inheritance

Sometimes you may need to override delegate methods. Consider the case of having two UIViewController subclasses: UIViewControllerA and UIViewControllerB, with the following class hierarchy.

UIViewControllerB < UIViewControllerA < UIViewController

UIViewControllerA conforms to UITableViewDelegate and implements - (CGFloat)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView heightForRowAtIndexPath:(NSIndexPath *)indexPath.

You want to provide a different implementation for the method above in UIViewControllerB. An implementation like the following will work:

- (CGFloat)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView heightForRowAtIndexPath:(NSIndexPath *)indexPath {

CGFloat retVal = 0;

if ([super respondsToSelector:@selector(tableView:heightForRowAtIndexPath:)]) {

retVal = [super tableView:self.tableView heightForRowAtIndexPath:indexPath];

}

return retVal + 10.0f;

}

But what if the given method was not implemented in the superclass (UIViewControllerA)?

The invocation

[super respondsToSelector:@selector(tableView:heightForRowAtIndexPath:)]

will use the NSObject's implementation that will lookup, under the hood, in the context of self and clearly self implements the method but the app will crash at the next line with the following error:

*** Terminating app due to uncaught exception 'NSInvalidArgumentException', reason: '-[UIViewControllerB tableView:heightForRowAtIndexPath:]: unrecognized selector sent to instance 0x8d82820'

In this case we need to ask if instances of a specific class can respond to a given selector. The following code would do the trick:

- (CGFloat)tableView:(UITableView *)tableView heightForRowAtIndexPath:(NSIndexPath *)indexPath {

CGFloat retVal = 0;

if ([[UIViewControllerA class] instancesRespondToSelector:@selector(tableView:heightForRowAtIndexPath:)]) {

retVal = [super tableView:self.tableView heightForRowAtIndexPath:indexPath];

}

return retVal + 10.0f;

}

As code as the one above is ugly, often it'd be better to design the architecture in a way that delegate methods don't need to be overridden.

Multiple Delegation

Multiple delegation is a very fundamental concept that, unfortunately, the majority of developers are hardly familiar with and too often NSNotifications are used instead. As you may have noticed, delegation and datasource are inter-object communication pattern involving only 2 objects: 1 delegant and 1 delegate.

DataSource pattern is forced to be 1 to 1 as the information the sender asks for can be provided by one and only one object. Things are different for the delegate pattern and it would be perfectly reasonable to have many delegate objects waiting for the callbacks.

There are cases where at least 2 objects are interested in receiving the callbacks from a particular delegant and the latter wants to know all of its delegates. This approach maps better a distributed system and more generically how complex flows of information usually go in wide software.

Multiple delegation can be achieved in many ways and the reader is dared to find a proper personal implementation. A very neat implementation of multiple delegation using the forward mechanism is given by Luca Bernardi in his LBDelegateMatrioska.

A basic implementation is given here to unfold the concept. Even if in Cocoa there are ways to store weak references in a data structure to avoid retain cycles, here we use a class to hold a weak reference to the delegate object as single delegation does.

@interface ZOCWeakObject : NSObject

@property (nonatomic, weak, readonly) id object;

+ (instancetype)weakObjectWithObject:(id)object;

- (instancetype)initWithObject:(id)object;

@end

@interface ZOCWeakObject ()

@property (nonatomic, weak) id object;

@end

@implementation ZOCWeakObject

+ (instancetype)weakObjectWithObject:(id)object {

return [[[self class] alloc] initWithObject:object];

}

- (instancetype)initWithObject:(id)object {

if ((self = [super init])) {

_object = object;

}

return self;

}

- (BOOL)isEqual:(id)object {

if (self == object) {

return YES;

}

if (![object isKindOfClass:[object class]]) {

return NO;

}

return [self isEqualToWeakObject:(ZOCWeakObject *)object];

}

- (BOOL)isEqualToWeakObject:(ZOCWeakObject *)object {

if (!object) {

return NO;

}

BOOL objectsMatch = [self.object isEqual:object.object];

return objectsMatch;

}

- (NSUInteger)hash {

return [self.object hash];

}

@end

A simple component using weak objects to achieve multiple delegation:

@protocol ZOCServiceDelegate <NSObject>

@optional

- (void)generalService:(ZOCGeneralService *)service didRetrieveEntries:(NSArray *)entries;

@end

@interface ZOCGeneralService : NSObject

- (void)registerDelegate:(id<ZOCServiceDelegate>)delegate;

- (void)deregisterDelegate:(id<ZOCServiceDelegate>)delegate;

@end

@interface ZOCGeneralService ()

@property (nonatomic, strong) NSMutableSet *delegates;

@end

@implementation ZOCGeneralService

- (void)registerDelegate:(id<ZOCServiceDelegate>)delegate {

if ([delegate conformsToProtocol:@protocol(ZOCServiceDelegate)]) {

[self.delegates addObject:[[ZOCWeakObject alloc] initWithObject:delegate]];

}

}

- (void)deregisterDelegate:(id<ZOCServiceDelegate>)delegate {

if ([delegate conformsToProtocol:@protocol(ZOCServiceDelegate)]) {

[self.delegates removeObject:[[ZOCWeakObject alloc] initWithObject:delegate]];

}

}

- (void)_notifyDelegates {

...

for (ZOCWeakObject *object in self.delegates) {

if (object.object) {

if ([object.object respondsToSelector:@selector(generalService:didRetrieveEntries:)]) {

[object.object generalService:self didRetrieveEntries:entries];

}

}

}

}

@end

With the registerDelegate: and deregisterDelegate: methods, it is easy to connect/disconnect cables between components: if at some point in time a delegate object is not interested in receiving the callbacks from a delegant, it has the chance to just 'unsubscribe'.

This can be useful when there are different views waiting for some callback to update the shown info: if a view is temporarily hidden (but still alive) it could make sense for it to just unsubscribe to those callbacks.